The answer, as with anything involving law and lawyers, is that it depends.

It depends on how you think lawyers should spend their time.

If you think lawyers should spend as much time as possible reading countless documents and manually tracking document versions, then yes. You should be very afraid of AI.

If you think a lawyer’s job is to solve problems for their clients, then you shouldn’t fear AI. In fact, you should be very excited about AI because your job is about to get a lot more exciting and interesting.

Before I dive in, let me tell you a bit about why you might consider my perspective on this worthwhile. My name is Kevin, and I studied law and computer science at Stanford. I read thousands of documents in M&A diligence as an associate at Simpson Thacher, and I worked on the search function at LinkedIn as a software engineer.

I run a tech startup and maintain a solo practice of law. I talk to both lawyers and computer scientists every day.

In other words, I think a lot about the question: what is AI and what does its arrival mean for lawyers?

The “Artificial Intelligence” that has folks excited these days is not exactly “intelligence”. It’s not the broadly intelligent AI from science fiction movies like Her or the Matrix. It’s really just software that can digest a huge amount of text and images and find patterns really well.

That was all it did, until recently.

In the past year, we’ve seen the emergence of software that can go a step further. Programs like GPT3 and Dall-E can find patterns really well and mix and match those patterns to create new things.

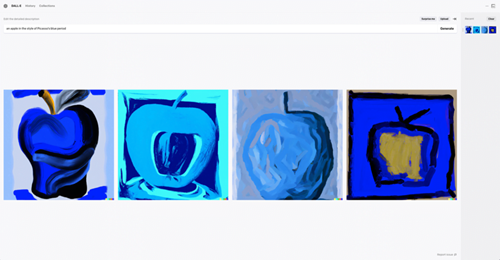

For example, you can ask Dall-E to “paint an apple in the style of Picasso’s blue period”.

Under the hood, Dall-E is “trained” on several million images of apples and paintings from Picasso’s blue period. Through its training, it captures essential patterns of both. Apples that are round and shiny, or perhaps brown and overripe. Paintings where all objects and shadows are blue.

Dall-E references these patterns when responding to your query. It combines what it knows of the form of an apple with the style of Picasso to create the following:

How does this relate to lawyering?

Can you think of any examples of lawyers spending a lot of time on tasks related to “find examples of pattern A, and present it to me in the style of pattern B”?

This is, in a nutshell, what all of litigation doc review and transactional diligence entails.

Based on what we’ve seen this year with Dall-E and GPT3, I would be surprised if any lawyers are manually conducting doc review and diligence five years from now.

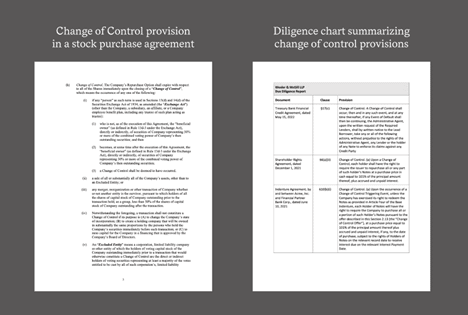

Diligence will soon entail asking the computer, “Find me all examples of a change of control provision, and present it to me in the style of this chart.”

The computer will simply do it better, faster, and with fewer errors.

Is this bad news for lawyers?

If you went to law school because you wanted to spend years of your life doing doc review, then I am sorry. You are about to lose one of your favorite parts of the job.

If you became a lawyer because you wanted to advise clients, craft legal theories, and negotiate agreements, buckle up because you’re about to be doing a lot more of that.

To help you share my excitement, let me tell you a bit about what Dall-E cannot do.

Imagine you ask Dall-E to “paint me a picture of the grand canyon, in an original style, that my spouse will love.”

The output? Chaotic:

Dall-E will struggle because two key parts of this prompt reference patterns that it cannot comprehend.

“In an original style” refers to a pattern that does not yet exist.

“That my spouse will love” refers to a pattern that the computer cannot read. Dall-E could try to trawl through your spouse’s social media to find patterns in their taste. But much of what a person “loves” is ineffable and not recorded by a machine-readable digital footprint.

Let’s relate this back to law.

A client asks, “draft me a contract for a unique joint venture with terms that both parties will accept.”

As with the painting, this prompt includes two key elements that a computer cannot comprehend.

“A unique joint venture” refers to a novel pattern, one that the lawyer must create.

“That both parties will accept” refers to preferences of the respective parties that a lawyer may discern through a combination of knowing their client, following market conditions, and negotiating with the counter party. While some of this information exists in text and images, much of it gets communicated verbally, through body language, and a general “feeling” about people.

I see absolutely no evidence that software will be able to comprehend this prompt any time soon.

Back to reality. Lawyers will soon spend most of their time solving novel problems for their clients that require judgment and creativity. I suspect this will come as good news to most lawyers.

There is more good news. The parts about lawyering that “AI” can do will make it a lot more fun for you to do the things that the computer cannot.

In the near future, you will spend 90% of your time thinking, drafting, advising clients, and negotiating. You will spend the other 10% of your time supervising software that automates the parts of your job that you currently find tedious.

You will instruct the computer,

“Find me ten examples of a joint venture agreement between a publicly traded, Canada-based financial services company and a Series C US-based fintech app development company.”

And whoompf! the computer will present you with ten relevant precedents to review.

You will then select your three favorite precedents and, with a few clicks, merge them into a single track changes document. You will reject and accept various provisions from each to create a composite document that you can use as the starting point for your drafting.

Incidentally, this is where my company’s software, Version Story comes into play. We make it effortless to compare multiple document versions and merge them into consolidated drafts.

From this base document, you will draft an original joint venture agreement that satisfies the unique needs of your client and that, in your judgment, the other party will accept. Negotiation and revisions will follow.

And just like that, you will continue lawyering as you always have. The biggest change? Using your lawyerly judgment now becomes the main thing you do.

‘But,’ you might still be wondering, ‘what if lawyers get so good at solving problems that society runs out of problems for lawyers to solve?’

Let’s evaluate this concern with an analogy to medicine.

Over the past hundred years, advances in medical technology have enabled doctors to quickly and effectively dispatch ailments that had stalked humanity through the ages. Did the polio vaccine put doctors out of work? Did MRIs eliminate the need for diagnosticians?

Doctors have not run out of problems to solve. Instead, medical technology has enabled doctors to provide what was once expensive, state-of-the-art care to the broader public at low cost. And it has freed up doctors’ time to focus on more complex and devious ailments.

Legal technology, infused with AI, will do the same for lawyers. As a profession, we might finally find the time to solve problems for the 80% of Americans who need a lawyer but cannot access one. And we might soon find ourselves in a world where junior lawyers, on their first assignment, craft theories about the application of First Amendment jurisprudence to novel situations.

Personally, I am excited to be a lawyer in this near-future. As always happens with technology, the future belongs to those who get ahead of the trend. So roll up your sleeves –– there’s work to do.