Non-traditional marks

Issues over non-traditional marks were hotly debated in 2017. Whilst the EU trade mark reform package paved the way for certain new types of marks to be registrable, issues continue to arise, in particular, in relation to the protection of shapes and packaging.

KitKat - Court of Appeal sets high bar for acquired distinctiveness

Most people in the UK would recognise the KitKat shape. Yet, in the long-running dispute between Nestlé and Cadbury, the Court of Appeal decided that the shape of Nestlé's four-finger chocolate bar does not have the necessary acquired distinctiveness to qualify for protection as a UK trade mark. The decision demonstrates how high the hurdles are for those seeking to establish distinctiveness in relation to inherently non-distinctive marks, such as the shapes of products and packaging. In the decision, the Court of Appeal stressed the significant distinction between recognition and association on the one hand (which is not enough), and perception as to exclusive origin on the other.

Nestlé had relied upon a survey which indicated that, when shown a picture of the product, and asked questions relating to source, at least half the respondents gave answers to the effect of "It's a KitKat". Whilst many might understandably consider this sufficient to demonstrate that the shape had acquired distinctiveness, the Court of Appeal decided that this evidence only demonstrated that consumers recognised and associated the shape with KitKat - and therefore with Nestlé - but no more than that. It did not satisfy the proper test to be applied, which had been laid down by the European Court of Justice (CJEU), namely whether consumers would perceive the shape as originating from a particular undertaking, and not from others.

Establishing the relevant perception in each case will depend upon how the mark has been used. Businesses need to consider very carefully the use they make of a particular mark - such as a shape - in order to promote a product. This will put them in a position to compile the necessary evidence to demonstrate that the shape qualifies for trade mark protection through acquired distinctiveness, including in any survey evidence.

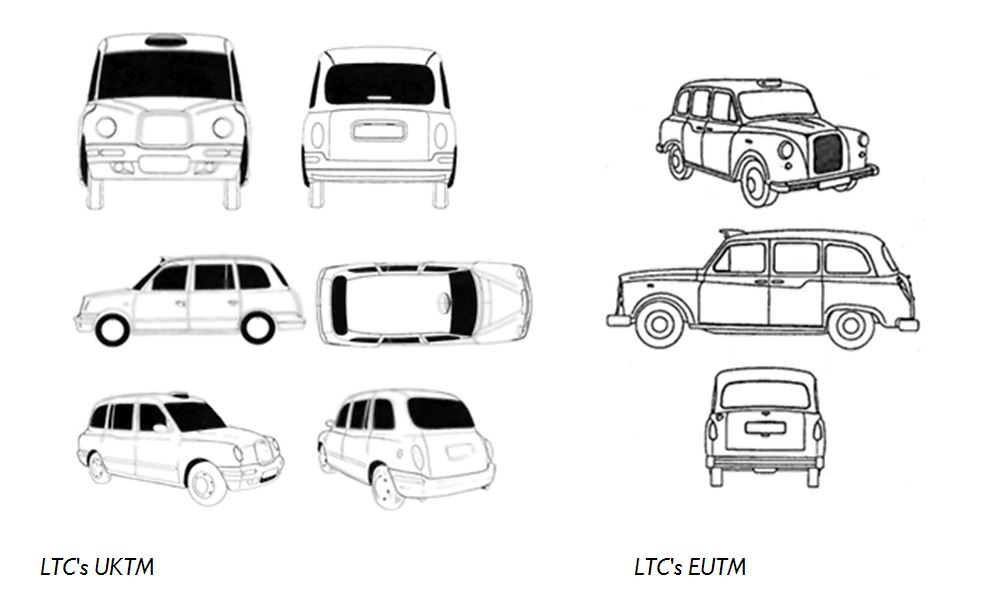

London black cab shape trade marks lack distinctive character

In a trade mark infringement dispute between LTC (the makers of London's iconic black cab) and the makers of the forthcoming hybrid electric taxi, the Metrocab, the Court of Appeal decided that the features of the shape of the London cab (such as the slope of the windscreen, the deep/high bonnet and the extended front grille) did not depart significantly from the norms of the car sector. As a result, LTC's trade marks were cancelled as the shape marks lack inherent distinctive character.

Applying the test laid down in KitKat, the marks also lacked acquired distinctiveness - adverts on flip-up seats in the cabs advertising the name of the manufacturer were not enough to educate the consumer that the shape of the taxi indicated its origin. There must be evidence from which it can be deduced that a consumer understands there is only one manufacturer of products of that shape.

It remains to be seen whether the Supreme Court will grapple with some of these issues relating to distinctiveness.

Protection of colour combination marks

Colour combination marks also faced difficulties in 2017, and it is not yet apparent whether things will be more straightforward under the EUTM reform package.

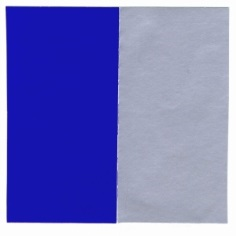

In November 2017, the EU General Court decided that Red Bull's well-known blue/grey colour combination was insufficiently precise to be validly registered as a trade mark. Subject to any appeal by Red Bull to the CJEU, the decision was a blow for brand owners, setting the test for registrability of two-colour marks very high. Indeed, the effect of the decision seems to be that colour marks comprising colour combinations are harder to register than those of single colours.

Red Bull's two trade mark applications included the following descriptions:

‘Protection is claimed for the colours blue (RAL 5002) and silver (RAL 9006). The ratio of the colours is approximately 50%-50%’.

‘The two colours will be applied in equal proportion and juxtaposed to each other’ (this wording was adopted following correspondence with the examiner).

The General Court decided that the combination of the representation with either description did not enable the sign to be precisely identified. Each description enabled some degree of ambiguity; the mere juxtaposition of colours, without shape or contour, did not exhibit precision and uniformity. Customers would be unable to use the mark as a badge of origin, and competitors would lack legal certainty as to the scope of protection provided by it.

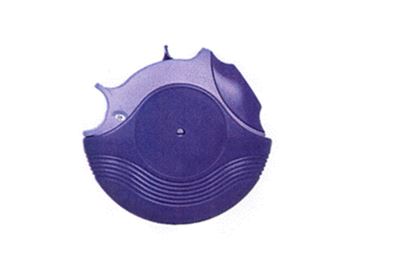

Meanwhile, in a dispute between Glaxo and Sandoz, the Court of Appeal decided that Glaxo's colour trade mark registration for its Seretide inhaler was invalid because it lacked the clarity, intelligibility, precision, specificity and accessibility required. The public, looking at the trade mark on the register would be in a position of 'complete uncertainty' as to what the protected sign actually was. The decision demonstrates the difficulties in filing colour combination trade marks but it also serves as a reminder of the potential value in passing off claims in enforcing trade mark rights in a colour or colour combination, as that claim continues before the Court.

Glaxo's registration was for the above visual representation, as well as a description, which read: "The trade mark consists of the colour dark purple (Pantone code 2587C) applied to a significant proportion of an inhaler, and the colour light purple (Pantone code 2567C) applied to the remainder of the inhaler."

Brand Portfolios: New types of EU marks now available

Significant changes to the EU trade mark regime came into force in October 2017, opening up a number of opportunities for brand owners to obtain protection for a range of new types of marks. Previously, a trade mark had to be capable of being represented graphically to be registered. This meant it was difficult to register marks such as sound or motion marks, with very few making it through to registration. It is now possible to apply for an EU trade mark even if it cannot be represented graphically (this development will also apply to UK marks, most likely from January 2019). Trade marks which can only be represented electronically (e.g. multimedia marks) may be accepted, and non-visual marks (e.g. sound marks) will also be easier to file.

However, marks will still be subject to the usual examination of whether they are distinctive in relation to the relevant goods and services. Whilst marks can be represented in any appropriate form using generally available technology, they must also be reproduced on the register in a manner which enables the public to identify what is protected with clarity and precision.

The list of protectable marks is not exhaustive and others may be added, given advances in technology and branding practices. An EU certification mark is also now available (some Member States already provided for national certification marks).

Trade mark infringement and validity highlights

Sales of "grey" goods can be a criminal offence

Criminal trade mark offences can apply not only to the distribution and sale of counterfeit goods but also to 'grey' goods, under the Supreme Court's ruling in R v C. Grey goods bear a registered trade mark and were produced with the trade mark owner's consent, but were never permitted to be released onto the market. In this case, the appellants unsuccessfully challenged a Court of Appeal decision that they could be prosecuted for unlawfully selling various branded goods, some of which were counterfeit and some of which were grey goods.

The decision also provides a strong argument that unauthorised parallel imports – that is, goods manufactured and sold with the trade mark owner's authorisation in a non-EU country but which have subsequently been imported and sold in the EU without consent – could also potentially be a criminal offence.

It will also allow brand owners to bring private prosecutions against anyone trading in grey goods, as well as counterfeits. Private prosecutions allow victims of crime greater control over the case and costs, and send a strong message to counterfeiters and those trading in grey goods, who face up to 10 years in prison where successfully convicted.

COTY - The CJEU sides with owners of luxury brands

In December 2017, the CJEU ruled that a supplier of luxury goods can prevent its authorised distributors - part of the supplier's selective distribution system - from selling those luxury goods via third-party platforms (the case concerned 'amazon.de').

In a judgment that will please luxury brand owners, the CJEU confirmed that properly constituted selective distribution schemes can be used to preserve the luxury image of luxury goods. The Court observed that an obligation imposed on authorised distributors to sell the luxury goods online solely through their own online shops and not via third-party platforms, provides the luxury brand owner with a guarantee that its luxury goods will be exclusively associated with the authorised distributors. It went on to say that such an association is one of the objectives behind a luxury brand owner setting up a selective distribution scheme for its products.

Whilst the position in respect of luxury goods has now been clarified, this does not mean that all brand owners can restrict sales of their products via third-party platforms. The German Competition Authority, for example, has consistently held that restrictions on internet sales via third-party platforms are not justified for mainstream, non-luxury brands.

The Coty judgment is unlikely to be the final word on this issue. Numerous questions still remain unanswered including: how will brand owners respond when operators of third-party platforms modify their websites to include a "luxury" section and voluntarily offer to adhere to brand owners' guidelines for the presentation of their goods? And what view will the CJEU take when it is asked to explain why "high-quality goods" should not be treated in the same way as "luxury goods"?

Unauthorised garage infringed BMW trade marks

Brand owners faced with the all too common problem of independent businesses using their marks in a way which suggests a commercial connection or affiliation welcomed a Court of Appeal decision that the use of BMW's registered trade marks by an independent garage on its staff uniform, van and Twitter handle was trade mark infringement and passing off. Each type of use created the impression that the garage's BMW repairing service was affiliated to BMW's network, or that there was a special relationship between them.

The Court drew a key distinction between misleading use and merely informative use. Whilst it would be acceptable for a business to say, for example, "The BMW specialists" or any use which conveyed the message "my business provides a service which repairs BMWs and/or uses genuine BMW spare parts", a message to the effect of "my repairing service is commercially connected with BMW" would amount to a false one. In each case, it will be necessary to consider the detail and the context of the use that is being made of the brand.

EUTMs: Unitary nature and co-existence

An EU trade mark is a unitary right, providing the proprietor with the same exclusive rights throughout the EU. However, what should happen where a mark and sign co-exist in one part of the EU, but there is a claim for infringement in another?

The owners of KERRYGOLD EUTMs claimed infringement in Spain for use of the sign KERRYMAID. The Alicante Commercial Court referred three questions to the CJEU, focusing on how to apply the peaceful coexistence of the mark and sign in the UK and Ireland to the Spanish proceedings. The CJEU decided, broadly, that the peaceful coexistence and geographical, demographic, economic or other circumstances prevalent in some Member States should form part of the global assessment of likelihood of confusion and due cause, but was not itself definitive. The court should have regard to the different market conditions and sociocultural circumstances between Member States. Accordingly, a trade mark proprietor can prevent infringement in any part of the EU, whether or not such infringement extends throughout the EU (and so, an agreement to co-exist in one part of the EU will not prevent an infringement claim in another).

Flynn prevents parallel imports of third party products bearing its brand

In a rare parallel import case, the Court of Appeal decided that a trade mark owner could prevent parallel imports of pharmaceutical products sold under its trade mark where the relevant goods were not put on the market by the trade mark owner, but by a third party. The decision focuses on the issue of 'control', which was material on the question of whether the trade mark owner could prevent the particular parallel imports.

The Court concluded that Flynn (the trade mark owner) did not have the ability to exercise control over the goods before they were placed on the market by the third party, Pfizer, in the exporting state. Further, the links between Flynn and Pfizer were not such that use of the Flynn trade mark was under Pfizer's control. Accordingly, Flynn's enforcement of its trade mark against parallel imports of products manufactured by Pfizer, and bearing Flynn's mark, would not breach free movement of goods provisions.

Mark referring to name of Macedonian village not invalid as geographical descriptor

Marks which designate a geographical origin cannot be registered if the geographical name is known to the relevant class of people as the designation of a place, and if it suggests (or could suggest) a current association with the good or services. However, a mark may acquire distinctiveness through use where the average consumer perceives the mark as identifying the goods or services as originating from a single undertaking. If a geographical name is very well known, it can only acquire distinctive character if the owner has made long-standing and intensive use of the mark.

In Mermeren v Fox Marble, the IPEC decided that Mermeren's mark for SIVEC was inherently distinctive. Mermeren extracts and sells marble from the Prilep region of Macedonia, including from a quarry near the small village of Sivec. It owns an EU trade mark for SIVEC in relation to marble. Fox, a UK company, also extracts and sells marble from the Prilep region, also under the mark "Sivec".

The relevant public, i.e. those in the EU who purchased marble, would not have heard of Sivec (as it is a little-known place), and so it did not inherently designate the geographical origin of the goods. Further, even if the mark, through its use in the period prior to registration, did designate the marble's geographical origin, by the time Mermeren applied for its trade mark, this had been reversed by use. This case demonstrates that, in certain circumstances, it is possible to acquire distinctiveness, and turn a mark from being a geographical descriptor into a trade mark (in this case in a period of two years, which is quite a low threshold).

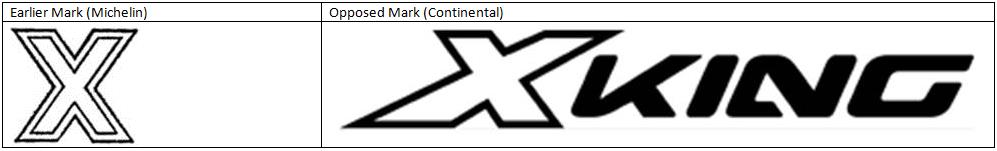

XKING crossed out by European Court of Justice

In a case which raises a number of issues for those looking to clear marks, the CJEU upheld a finding of a likelihood of confusion between an application by German tyre company Continental for the mark XKING with Michelin's earlier French registration for a stylised letter X. Both marks covered identical or highly similar goods relating to tyres.

The CJEU rejected the argument that a single letter element of a sign constitutes, as a general rule, a weakly distinctive element of a sign. Whilst there are certain categories of signs, including single letters, which are less likely to have distinctive character initially, the CJEU said there was not a general, abstract rule that the distinctiveness of such letters must, in all cases, be considered to be weak. Single letter marks, including those featuring a limited degree of stylisation, should therefore be considered seriously when identified in clearance searches, as they will not automatically be presumed to be weak.

Distinctive to the maxx

Whilst it was based on consistent reasoning, this General Court decision was noteworthy because the Opponent found it easy to establish rights in a sign that seems widely used in the English language to refer to the laudatory word "maximum". The decision serves as a reminder of the potentially unexpected linguistic differences that can occur in different EU Member States and which can be crucially important in clearing trade marks for wider use and registration in Europe.

The EU General Court decided that an earlier registration of the word mark MAXX in Bulgaria was sufficient to prevent registration of a similar mark which featured the suffix "-MAXX" as an EUTM. The Opponent owns the T.K MAXX brand and the application was for a stylised form of NARAMAXX:

The Naramaxx Mark

The key issue was whether the visual, phonetic and arguable conceptual differences between the earlier mark MAXX and the Naramaxx Mark were sufficient to avoid a likelihood of confusion. In particular, was the element "MAXX" sufficiently distinctive so that its mere inclusion as part of the Naramaxx Mark was enough to establish a likelihood of confusion?

The Court decided that the sign MAXX had no conceptual meaning for Bulgarian consumers. There was no laudatory connotation as the term "maxx" would not be understood to refer to the word "maximum". It was notable that Bulgaria uses the Cyrillic alphabet. It went on to conclude that there was a likelihood of confusion.

Pizza mark invalid on the basis of earlier use in a particular locality

The Court of Appeal has upheld a finding of invalidity in relation to the trade mark CASPIAN in a dispute between the operators of a Birmingham chain of restaurants and a Worcester restaurant, both called 'Caspian Pizza'. The Claimants' trade mark, CASPIAN, was found to be invalid based on the Defendant's earlier use in Worcester, which would have meant it could have succeeded in an action for passing off. Whilst the earlier use was only in Worcester, the Court confirmed that an opposition based on earlier use of a mark did not have to be use throughout the UK, or even in a geographical area which overlaps with the place where the trade mark applicant actually carries on business using the same or a similar mark. Accordingly, goodwill (as opposed to reputation) established in a particular locality may be capable of preventing registration of a countrywide trade mark.

Online infringement

Supreme Court to consider costs of website blocking orders

In 2016, the Court of Appeal confirmed that orders can be made against ISPs requiring them to block their customers from accessing websites selling counterfeit products, upholding an order in relation to six websites selling counterfeit Cartier and Mont Blanc products.

The Court of Appeal's decision extending this jurisdiction to websites selling counterfeit products based on trade mark infringement was a significant development for brand owners in their ongoing fight against counterfeiting but, to date, there has not been a raft of similar applications by brand owners. This is no doubt due to the outstanding appeal which will be heard by the Supreme Court in January 2018. The appeal will not focus on whether such orders can made as that is a settled issue; instead it will focus on who should bear the costs of implementing the website blocking order, the brand owner or the ISP?

Trade mark infringement for using Claimant's Amazon listings

The Courts continue to deal with new issues presented by technology, and different methods of selling and marketing goods and services. The Intellectual Property Enterprise Court issued an interesting decision in Jadebay v Clarke-Coles finding that the Defendant's use of the Claimant's Amazon listing for its flagpole products (flagpoles 'by DesignsElements') was trade mark infringement of the Claimant's 'Design Elements' trade mark on the basis of a likelihood of confusion, and passing off. The Defendant's products are sourced and purchased from a different manufacturer in China to that used by the Claimants and are different in design, but of comparable quality. The case is on appeal to the Court of Appeal.

No trade mark infringement for use of a domain name in conjunction with adverts

In Argos Ltd v Argos Systems, the Court decided that Delaware company Argos Systems' use of ARGOS in its domain name in conjunction with the display of advertisements under the Google AdSense programme did not infringe Argos' EUTMs for ARGOS. The complaint had been on the basis that the use was directed at UK users because adverts displayed in Google AdSense were of interest to UK consumers (some of the adverts were for Argos) and allowed Argos Systems to generate advertising revenue. Some 89% of traffic to the Defendant's argos.com website was from the UK, and 85% of UK visitors left the website after 0 seconds, with almost none clicking past the landing page. The case is on appeal to the Court of Appeal and will be heard in July 2018.

The Court decided that, as Argos had also signed up to the Google AdSense program, it had under its terms consented to Argos Systems' use of the sign in its domain name, together with the advertisements. On the question of targeting, the Court concluded that UK users would not regard the adverts as directed at them because they appeared on a page which they would not regard as directed to them.

Merck v Merck: Global website targeted UK consumers

The Court of Appeal also considered the question of targeting in Merck KgaA (Merck Global) v Merck Sharp & Dohme (Merck US) in a dispute concerning a claim for breach of contract and trade mark infringement relating to online use by Merck US of the word MERCK. The Court decided that the use either as a trade mark or company name was in breach of a 1970 Agreement between the two parties, which provided that Merck US should not use MERCK outside of the US.

On the issue of targeting consumers in the UK, the Court noted that Merck US's web presence was an integrated group of websites which were accessible by and directed at users in the UK and other countries. The architecture of the sites was also such that users accessing the 'msd-uk' site were directed to the 'merck.com site'. Visitor numbers were also material – the sites were not visited by 'strays', but by non-US residents in search of information and who had been directed or drawn to the merck.com site.