Following its decision earlier this year that the shape of one of the UK's best-selling chocolate bars, KitKat, did not have the necessary acquired distinctiveness to qualify for protection as a trade mark, the Court of Appeal has reached the same conclusion on the shape of another iconic UK product, the London black cab.

In a trade mark infringement dispute between LTC (the makers of the black cab) and the makers of the forthcoming hybrid electric taxi, the Metrocab, the court has decided that the features of the shape of the London cab (such as the slope of the windscreen, the deep/high bonnet and the extended front grille) do not depart significantly from the norms of the car sector. As a result, LTC's trade marks were cancelled as the shape marks lack inherent distinctive character.

Further, adverts on flip-up seats in the cabs advertising the name of the manufacturer were not enough to educate the consumer that the shape of the taxi indicated its origin. There must be evidence from which it can be deduced that a consumer understands there is only one manufacturer of products of that shape.

Whilst the case is a further reminder of the difficulties in registering shapes as trade marks (as opposed to obtaining design protection), it is possible that the case will go further to the Supreme Court. It raises a number of interesting issues, including the proper tests for assessing inherent distinctive character of shape marks, and whether a particular shape gives substantial value to the goods.

Background

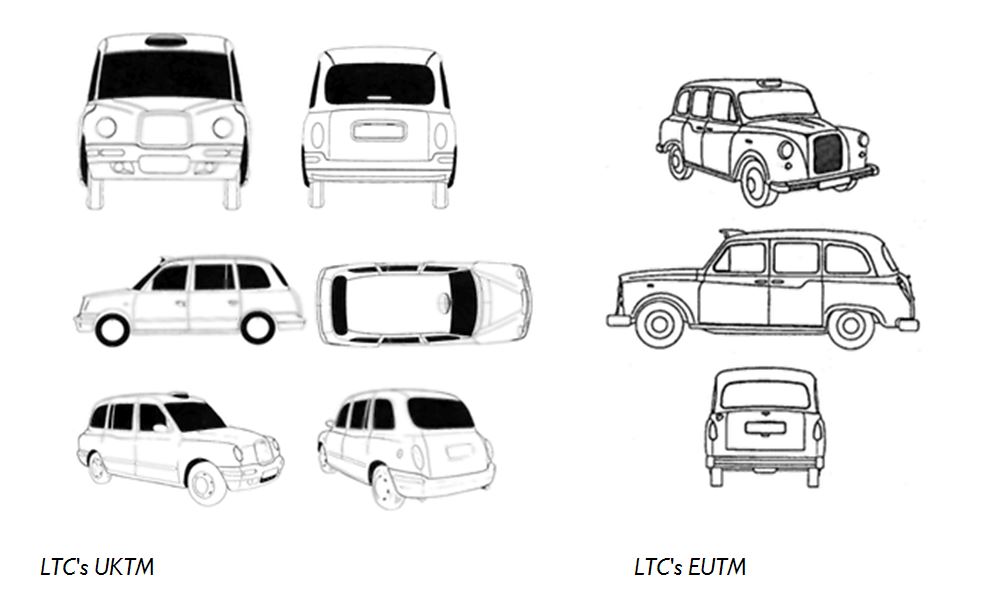

The London Taxi Corporation (LTC) owns UK and EU Trade Marks depicting the shapes of its iconic Fairway and TX1/TX11 models. LTC also owns a registered design for its TX1 model but the claim only covered its trade mark rights.

Frazer-Nash Research's first Metrocab was launched in 1986 but the case centred on its much publicised plans to launch a hybrid electric taxi (its chairman described it as "instantly recognisable as an iconic London Hackney Cab…"). LTC sued for trade mark infringement and passing off, but both the trial judge and the Court of Appeal decided that its trade marks did not have inherent or acquired distinctiveness.

The Court of Appeal considered a number of aspects of trade mark law, and suggests that further clarification is needed on certain issues.

Who is the average consumer?

In addition to taxi drivers, should those that hire and ride in taxis be treated as consumers of taxis? Whilst the trial judge had thought they should not, the Court of Appeal stressed that the average consumer included any class of consumer to whom the guarantee of origin was directed and who would be likely to rely upon it, for example in making a decision to buy or use the goods: accordingly, it did not matter if the user was someone who merely hired the goods under the overall control of a third party. Although the court did not have to reach a concluded view on this issue, its leaning towards including, as the relevant consumer, people who use but do not buy the product is a welcome development for brand owners of certain goods.

Do the marks have inherent distinctive character?

LTC argued that a mark which departs significantly from the norms and customs of the relevant sector will necessarily possess distinctive character. It relied on case law from the European Court of Justice (CJEU) which suggests this is sufficient, but the English Court of Appeal had reached a different result in Bongrain. The Court of Appeal saw the force in LTC's arguments, but felt this was an issue the CJEU would have to determine in due course. No reference to the CJEU was necessary in this case, however, because the marks did not depart significantly from the norms and customs of the car sector. For example, LTC relied upon a number of features including the size and slope of the windscreen, the deep/high bonnet, the extended prominent front grille etc. However, these were no more than a variant on the standard design features of a car: "a windscreen has a slope, a bonnet has a height and a grille has a shape". This cursory dismissal of the features of the traditional London taxi, which most people might consider fairly distinctive, suggests that a car design would have to be very radical indeed to ever possess inherent distinctive character.

That said, the court's consideration of this issue does give some hope that a design which departs significantly from the norms of the sector will be sufficient for inherent distinctiveness.

Do the marks have acquired distinctiveness?

This was the major area of dispute. The Court of Appeal considered the appropriate test for acquired distinctiveness in KitKat it is not enough for the trade mark owner to show that a significant proportion of the relevant class of persona recognise and associate the mark with its goods. It must show that they perceive that the goods designated by the mark originate with a particular undertaking and no other.

LTC had taken a number of steps in an attempt to educate the public as to the trade mark significance of the shape, including adverts on the flip-up seats in the taxi identifying the manufacturer. However, even if hirers of taxis were included as an average consumer (as well as the taxi drivers themselves), their focus would be on the provider of the service (the driver), and not the manufacturer of the vehicle. There had to be evidence from which it could be deduced that consumers understood there was only one manufacturer of taxis of that shape, and the evidence simply was not sufficient.

Following on from the KitKat decision, this case reinforces the difficulty of proving acquired distinctive character for shape trade marks. As the court said, "one must remember, as always in the case of a shape mark, that the public are not used to the shape of a product being used as an indication of origin."

Remaining issues

Due to the court's conclusions on distinctive character, it did not have to consider the remaining issues. However, it expressed the following views:

- Did the shape give substantial value to the goods?

This exception to trade mark protection has been notoriously difficult to interpret. If it had been necessary, the Court of Appeal would have referred questions to the CJEU on (1) whether, in addressing substantial value, you should take into account or ignore the fact that consumers will recognise the shape as that of a London taxi (2) the relevance of the presence/availability of design protection.

- Non-use and second-hand goods

In principle, second hand sales of the Fairway model by the trade mark proprietor could amount to genuine use of that trade mark.However, because production of the Fairway had long ceased (and even second hand sales of it had recently dried up), the sales were not sufficient to "create or preserve a market" for the goods protected by the trade mark. Accordingly, the trade mark, had it been valid, would have been revoked for non-use.

- Infringement and passing off

The Court of Appeal would have decided there was no passing off and no trade mark infringement on the basis of a likelihood of confusion. In particular, it thought the differences between the marks and the new Metrocab design were 'striking'. However, if it had accepted the marks had distinctive character, the court would have concluded that there was infringement on the basis of detriment to distinctive character.

Related Articles

Daily Mail

World Intellectual Property Review

World Trade Mark Review