Frauds where individual investors are duped into giving money to fraudsters impersonating legitimate “clone” financial institutions are on the rise in the UK. Enforcement against these crimes is unsatisfactory, with devastating consequences for the victims and potential reputational issues for the impersonated firms. Many are turning to civil and private criminal options available to tackle the issues alongside traditional responses.

Investment fraud on the rise

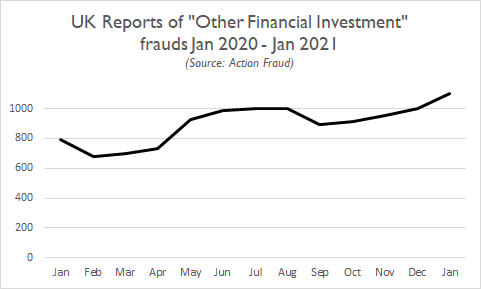

Figure 1 - UK investment fraud reports

The UK financial services regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), issued a warning at the end of January that investment frauds resulted in £78 million in losses in 2020. Investment frauds rose 29 percent from March to April 2020, coinciding with the national coronavirus lockdown. Over this time, investors have also been increasingly concerned by economic conditions and looked for higher returns than the very low interest rates offered by many financial institutions.

In 2020, there was a marked rise in investment fraud reports to the UK Action Fraud body, showing a marked and sustained increase in the number of reports from around April 2020 onwards, although these may be the tip of the iceberg. The National Crime Agency in the UK estimates that under 20 percent of frauds are reported. Of those frauds that do get reported, even fewer get investigated or prosecuted. Figures from the Office of National Statistics estimate the number of all frauds committed to be 4.4 million from September 2019 to September 2020, with the CPS only prosecuting a small fraction of that figure.

Cyber-enabled fraud

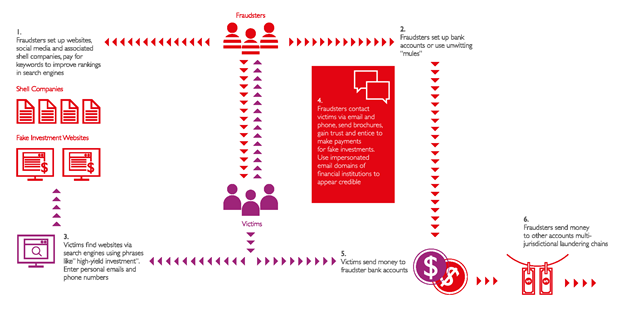

Figure 2 - Anatomy of an investment fraud

Our own experience of investigating investment frauds suggests the schemes are increasingly facilitated by the use of websites and search engines to promote these pages. In our State of Cybercrime 2020 report, we looked at the typical steps in an investment fraud. Characteristically, fraudsters set up websites typically posing as brokers, who promote the investment opportunities. Shell companies are also set up and referenced on the websites to lend credibility to the sites. Victims search for investment opportunities online, drawn to high promised rates of return and then provide their contact details to the site by registering an interest. The fraudsters then may call or email the investors, posing as a legitimate financial institution and share bogus documentation to gain the trust of their victims, before deceiving them into making a fraudulent bank transfer. This reliance on internet infrastructure is likely due to the anonymity it can afford and often means that victims have no way of identifying the fraudsters or taking action against them. The complexity and cost of investigating these kinds of frauds can be a barrier for police forces. While losses are often large in aggregate, the individual losses to victims do not reach thresholds which are prioritised for investigation.

A “whole system” approach

Investment frauds typically target members of the public, often older people looking to invest pensions or wealth amassed over their lifetimes. Even so, some impersonated institutions are also doing more to protect the public, not just by notifying regulators and issuing warnings to their customers, but by launching investigations, taking down websites and taking civil action to uncover evidence which can be used by police, if appropriately permissioned.

The UK enforcement response to fraud is lacking due to competing priorities and lack of appropriately trained and resourced police. While steps have been taken to coordinate between fraud bodies, such as the National Economic Crime Centre (NECC), more needs to be done to address the issues. In a recent paper, the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) argued that fraud had reached “epidemic” levels and that a centrally coordinated national response was needed, which recognised the threat of fraud to the UK as a danger to national security. The researchers also argued that a “whole system” approach should be adopted to tackling the problem, such as involving multiple government agencies. They also noted the potential for private firms to contribute in areas where the police lack capability or capacity, such as recovering funds or bringing private prosecutions.

MDR Cyber and Mishcon de Reya have worked to help the victims of fraud and impersonated firms to minimise risks and contribute to enforcement efforts. Our online investigations capability is enhanced by the ability to “unlock closed doors” such as using legal disclosure orders to compel banks to provide information on account holders and taking disruptive action against the websites, emails and phone lines used by the fraudsters to facilitate their scams.

If fraud continues to increase at the alarming levels we have seen in the past 12 months, more will need to be done to protect the victims and the reputations of the firms that have been impersonated. While launching private action will not remove many of the economic and social drivers of the increase in fraud, it will go some way to tackling the issues, while also helping victims make financial recoveries and holding fraudsters to account.